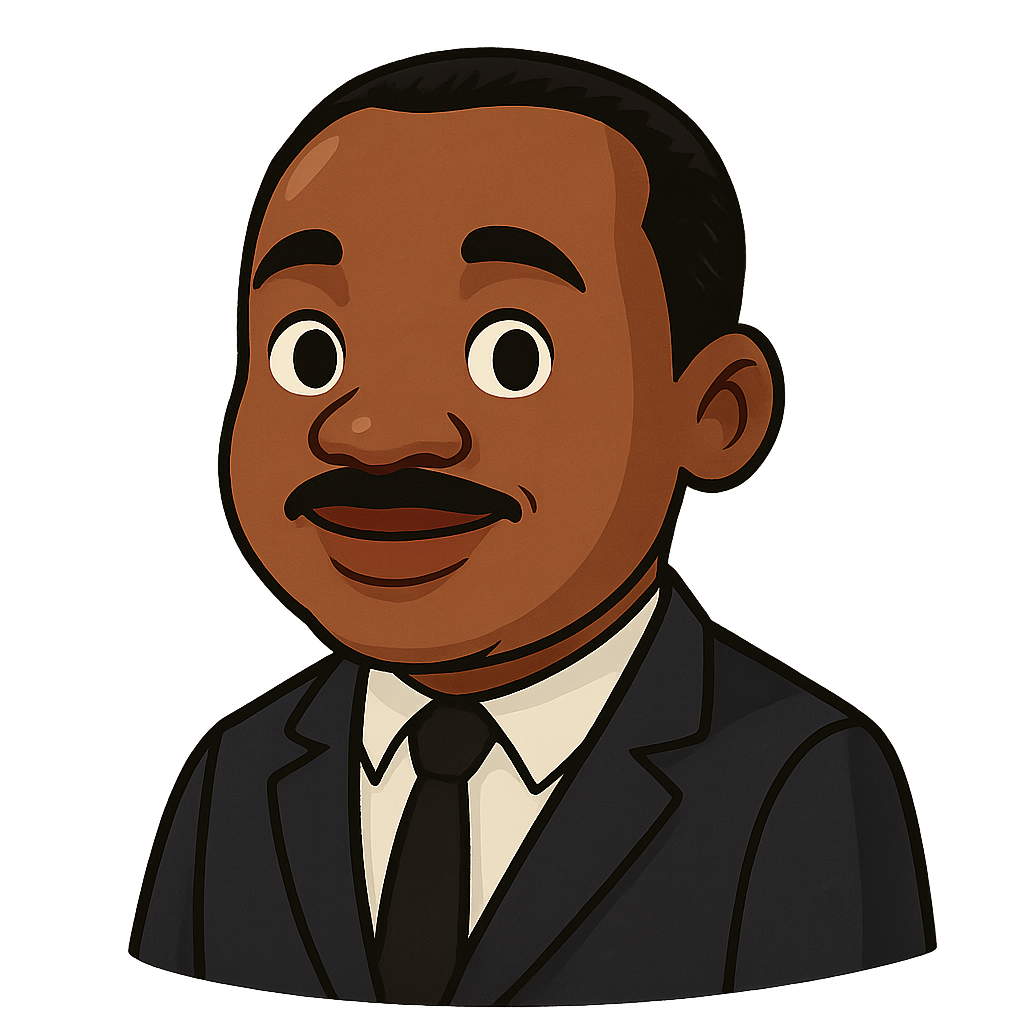

Martin Luther King Jr.: A Dream of Freedom

My name is Martin Luther King Jr., and I want to tell you my story. I was born on January 15, 1929, in Atlanta, Georgia. My world was centered around my family and the Ebenezer Baptist Church, where my father was a pastor. I had a happy childhood, filled with love from my parents, my older sister Christine, and my younger brother A.D. We played games and had fun just like any other children. But outside my home, the world was a very different place. Atlanta, like much of America at that time, was a segregated city. That meant there were separate, and unequal, rules for Black people and white people. I didn’t understand this until I was six years old. I had a white friend, and we were the best of playmates. But one day, his father told him he couldn’t play with me anymore. When I asked my parents why, they sat me down and explained the history of slavery and the unjust laws of segregation. I remember the hurt and confusion I felt. That day, a fire was lit inside me—a desire to see a world where people wouldn’t be judged by the color of their skin.

That desire for justice stayed with me as I grew older. I loved to learn and I loved words. I believed that words had the power to change hearts and minds. I worked so hard in school that I skipped two grades and started my studies at Morehouse College in 1944, when I was only fifteen. I decided to become a minister, just like my father and my grandfather before him. I wanted to help people and fight against the unfairness I saw all around me. My quest for knowledge didn't stop there. I went on to study at Crozer Theological Seminary in Pennsylvania and then to Boston University to earn my doctorate degree. It was during my studies in 1953 that I learned about a great leader from India named Mahatma Gandhi. He had freed his country from foreign rule not with weapons, but with a powerful idea he called nonviolent resistance. He taught that you could fight injustice with peace, love, and courage. His philosophy connected deeply with my Christian faith, which taught me to love everyone, even my enemies. I knew then that this was the path I had to follow. It was also in Boston that I met a remarkable woman named Coretta Scott. She was studying music and had a strength and grace that I admired deeply. We married in 1953, and she became not just my wife, but my partner in the struggle for equality.

In 1954, with my studies complete, Coretta and I moved to Montgomery, Alabama. I became the pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church. Montgomery was a city where segregation was a harsh daily reality. One of the most painful examples was the city bus system. Black people were required by law to pay their fare at the front, get off, and re-enter through the back door. They also had to give up their seats to white passengers if the front section filled up. This injustice came to a breaking point on December 1, 1955. A brave seamstress named Rosa Parks was sitting in the “colored” section when the bus driver demanded she give her seat to a white man. She calmly refused. She was arrested for breaking the segregation law. Her arrest sparked a fire in the Black community. We knew we could no longer accept this humiliation. Community leaders asked me, a young pastor of 26, to lead a protest. We decided to organize a boycott of the city buses. For 381 long days, about 50,000 African Americans in Montgomery refused to ride the buses. We walked miles to work, organized carpools, and supported one another through exhaustion and fear. Our homes were threatened, but we never gave up. Finally, on November 13, 1956, our peaceful protest was victorious. The U.S. Supreme Court declared that segregation on public buses was unconstitutional. We had shown the world that people, united in nonviolent action, could change unjust laws.

Our victory in Montgomery was just the beginning. The Civil Rights Movement grew, and we organized nonviolent protests across the South. We knew the path would be difficult. In 1963, we focused our efforts on Birmingham, Alabama, one of the most segregated cities in the nation. During the protests there, I was arrested and placed in solitary confinement. It was there, on scraps of paper, that I wrote my “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” explaining to the world why we could not wait for justice any longer. Later that year, on August 28, 1963, we held the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. It was an incredible day. More than 250,000 people—Black and white, from all walks of life—gathered peacefully at the Lincoln Memorial. I stood before that crowd and shared my vision for our country. I spoke of my dream that one day my four little children would live in a nation where they would not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character. The following year, in 1964, I was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. I was deeply humbled. I accepted the award not for myself, but on behalf of every single person who was part of our movement, who chose love over hate and peace over violence.

My journey was filled with hope, but it was also filled with great danger. Fighting for what is right often comes at a high cost. On April 4, 1968, while I was in Memphis, Tennessee, to support striking sanitation workers, my life was taken from me. I was only 39 years old. But even though my time on this Earth came to an end, the dream I shared did not. A dream of justice, equality, and peace can never be silenced. Think of it like a relay race. I carried the baton of freedom as far as I could, and now it has been passed to new generations. It is in your hands now. I ask you to carry it forward by treating everyone with dignity, by speaking out against unfairness, and by working to build a more just and peaceful world for all people. The work continues, and the dream lives on in you.

Reading Comprehension Questions

Click to see answer